February 2026

A galaxy is said to be active if its central supermassive black hole accretes matter from its environment at a high rate, forming an accretion disk. This accretion of matter onto the black hole is sometimes (for about 10% of active galactic nuclei, AGN) accompanied by the ejection of powerful jets: highly collimated particle outflows, streaming away from the central engine at almost the speed of light. If one of the relativistic jets points in the direction of the observer at a small angle, the AGN is called a blazar. The close alignment of the jet along with its highly relativistic motion greatly enhances the observed emission from blazars, by factors of thousands or more. From some blazars we observe very-high-energy (VHE) γ-ray emission, with photon energies exceeding 100 GeV (i.e., 100 billion times more energetic than visible light) – these can be studied with the H.E.S.S. telescopes.

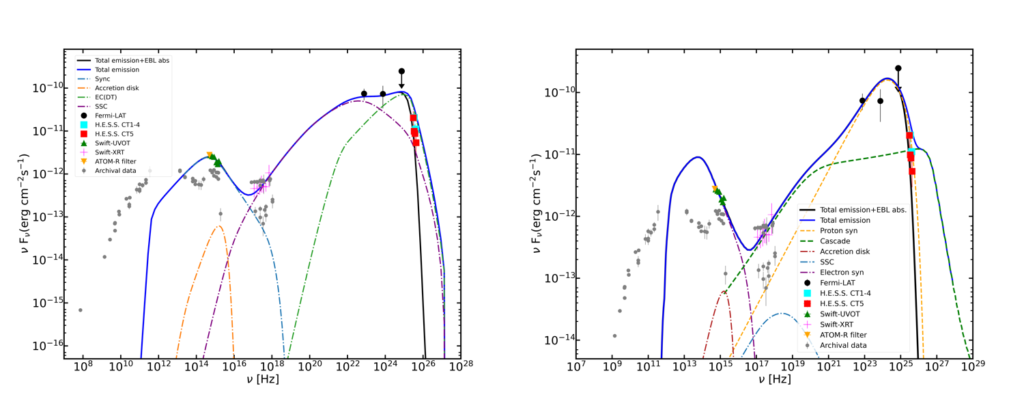

Blazars are classified into two categories; flat-spectrum radio quasars (FSRQs) and BL Lacertae objects (BL Lacs), which differ in the properties of the emitted radiation. For both types, the spectral energy distribution (SED) shows a double-peaked structure with a low-energy component typically ranging from radio waves to the optical / ultraviolet and a high-energy component from X-rays to γ-rays. Although the low-energy component is well explained by synchrotron emission (produced when highly relativistic charged elementary particles move in a magnetic field) from relativistic electrons in the jet, the emission processes responsible for the high-energy component are still a puzzle. In leptonic models, the same electrons that produce the low-energy synchrotron component also produce the high-energy emission via Compton scattering. Alternatively, in hadronic models, protons may also be accelerated to ultra-relativistic energies and contribute to the high-energy emission through proton synchrotron emission and/or proton-photon interactions. Some sources have been successfully modelled with both leptonic and hadronic models [1].

The detection of VHE γ-rays from distant blazars is limited as γ-ray photons at those energies interact with low-energy photons from diffuse extragalactic background light (EBL) leading to electron-positron pair-production [2]. This interaction leads to an attenuation of the observed VHE γ-ray flux, which becomes more severe with both increasing distance and photon energy. For this reason, no blazar has so far been detected in the VHE domain at a redshift exceeding z = 1 (corresponding to a distance half-way through the observable Universe). This limitation motivates an on-going observing programme by the H.E.S.S. observatory to follow-up on blazars at redshifts near or above z = 1, seen to be flaring in high-energy (HE, E > 100 MeV, i.e., more than 100 million times more energetic than visible light) γ-rays by the Large Area Telescope onboard the Fermi Gamma-Ray Space Telescope (Fermi-LAT).

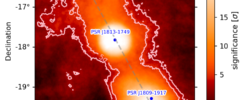

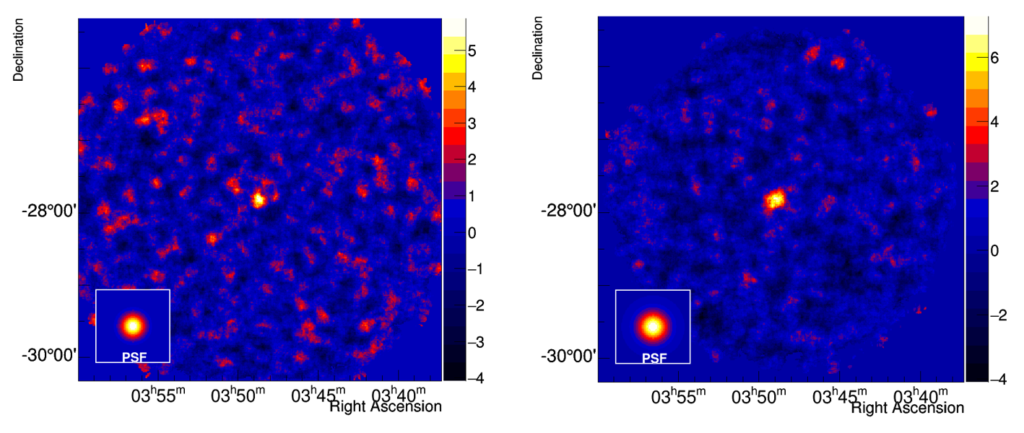

As part of this high-z blazar target-of-opportunity (ToO) programme, H.E.S.S. observed the z = 0.991 FSRQ PKS 0346–27 from 30 October to 8 November 2021, in response to a flare alert from Fermi-LAT. These observations led to a significant detection of the blazar [3], making PKS 0346–27 the most distant blazar ever detected with a ground-based γ-ray observatory at the time. The source was only detected in one night, namely on 3 November 2021. Figure 1 shows the significance maps for both the CT1-4 (the four 12-m diameter telescopes) and the CT5 (the 28-m diameter telescope) datasets on the detection night.

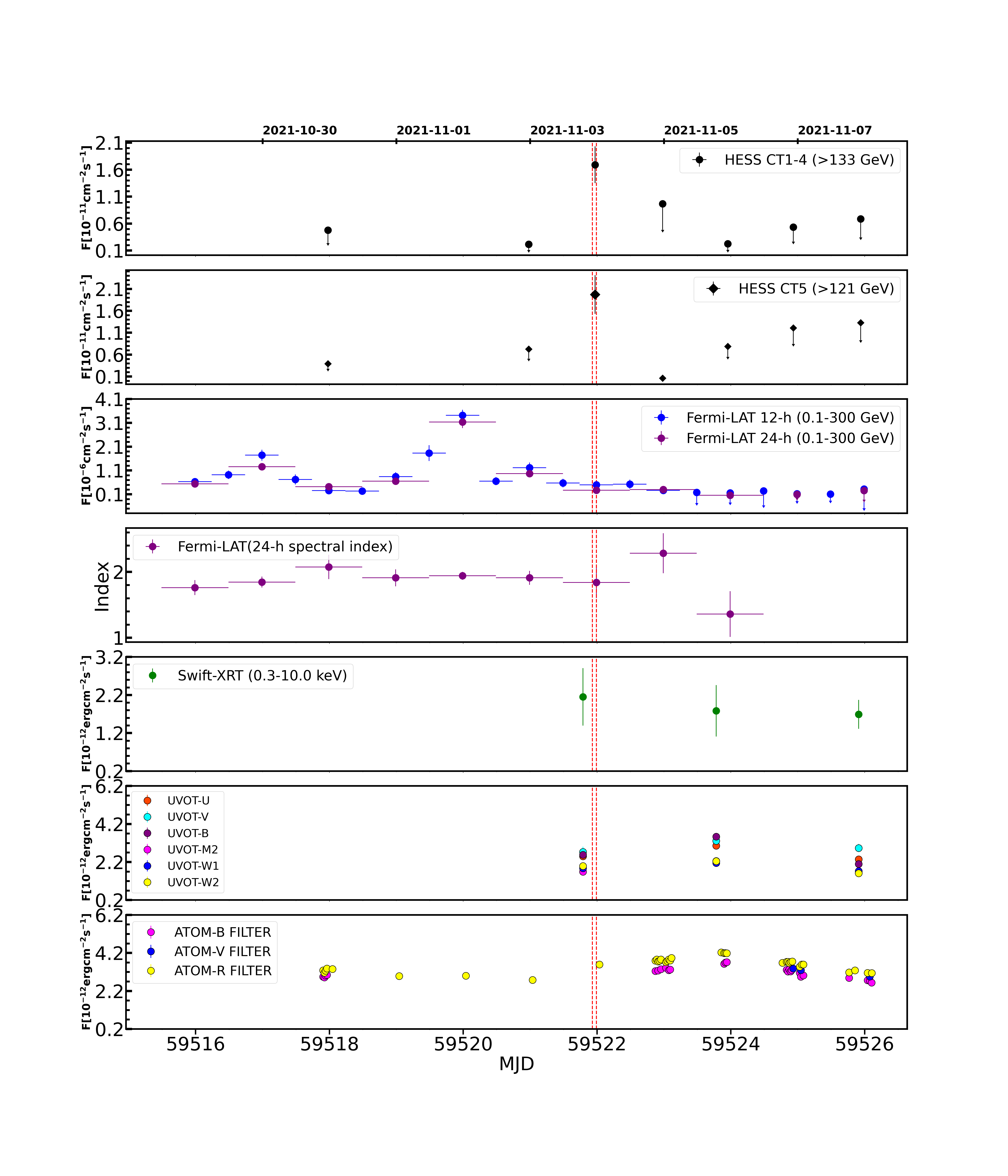

The H.E.S.S. observations were supplemented by multi-wavelength observations with Swift-XRT in X-rays, and the Automated Telescope for Optical Monitoring (ATOM) and Swift-UVOT in the optical and UV bands. Figure 2 shows the multi-wavelength light curves. Due to bad weather, no H.E.S.S. observation was possible during the two HE γ-ray lightcurve peaks detected with Fermi on October 30 and November 1 (third panel). Notably, when the source was flaring in the VHE band on November 3 (H.E.S.S. data, top 2 panels), the HE γ-ray lightcurve showed the source already back in quiescence, i.e., the VHE γ-ray flare was not coincident with flaring in the adjacent HE γ-ray band. Such a delayed VHE γ-ray flaring behavior is very difficult to reconcile with the simplest blazar emission models, which usually assume just one dominant emission region in the jet responsible for the entire emission.

One possible scenario that explains such a delayed VHE flare is the hadronic synchrotron mirror model [4]. In this model, synchrotron photons produced in the emission region at the time of the HE flare are reflected by external matter, e.g., a cloud, back into the emission region and may serve as an enhanced target photon field for either Compton scattering or proton-photon interactions, thus plausibly leading to HE or VHE flaring without a counterpart at lower energies. An alternative explanation could be a slow acceleration process – as observed recently in a Galactic nova [5] – due to which the highest-energy particles, producing the VHE γ-rays, reach the required energies with an (observed) delay of ~2 days. However, both the synchrotron-mirror and the slow-acceleration scenarios face problems, as elaborated in the full H.E.S.S. collaboration paper in Astronomy & Astrophysics reporting on this discovery.

When modeling the SEDs of blazars, one usually starts out with the simplest possible model with the fewest number of free parameters, which is a single-zone leptonic model. Although a satisfactory fit with a leptonic model was, in principle, possible (left panel of Fig. 3), it required extreme values of parameters, not usually found in FSRQs, such as very high Doppler and bulk Lorentz factors of ~80 and a very low magnetic field, leading to the jet having a very low magnetization, which leads to problems with keeping the particles confined within the jet. Alternatively, a satisfactory fit to the SED could be obtained with a single-zone hadronic model (right panel of Fig. 3) with parameter values compatible with other blazars. Therefore, a hadronic fit is considered to be preferred for PKS 0346–27.

Meanwhile, another blazar, OP 313 at a slightly higher redshift of z = 0.997 was detected by the prototype Large Sized Telescope (LST-1) of the Cherenkov Telescope Array Observatory [6]. This and other discoveries of high-z blazars will help us to gain deeper insights into the acceleration mechanisms in the extreme environments of blazar jets. At the same time, a larger sample of blazars at large distances will allow us to better constrain the properties of the EBL.

References

[1] M. Böttcher, A. Reimer, K. Sweeney, and A. Prakash. Leptonic and Hadronic Modeling of Fermi-detected Blazars. Astrophysical Journal 768, 54 (2013).

[2] M. Salamon and F. Stecker. Absorption of High-Energy Gamma Rays by Interactions with Extragalactic Starlight Photons at High Redshifts and the High-Energy Gamma-Ray Background. Astrophysical Journal 493, 547 (1998).

[3] S. Wagner and B. Rani. Astronomer’s Telegram #15020, 2021.

[4] M. Böttcher. A Hadronic Synchrotron Mirror Model for the “Orphan” TeV Flare in 1ES 1959+650. Astrophysical Journal 621, 176 (2005).

[5] H.E.S.S. Collaboration. Time-resolved hadronic particle acceleration in the recurrent nova RS Ophiuchi. Science 376, 77–80 (2022).

[6] J. Cortina. Astronomer’s Telegram #16381, 2023.