January 2026

Earth is constantly bombarded by highly energetic particles from space, known as cosmic rays. Since their discovery, the question of their origin and acceleration mechanism has been one of the central questions in high‑energy astrophysics. These particles reach energies far beyond those achievable in human‑made accelerators, and over the decades, a variety of astrophysical objects have been proposed as extraordinarily efficient acceleration sites, from the remnants of exploded stars to the centres of active galaxies, each offering extreme environments where particles can be boosted to relativistic energies. Understanding where and how this acceleration takes place remains key to uncovering the origin of cosmic rays in our Galaxy.

Among the most efficient particle accelerators in the Galaxy are pulsars: rapidly rotating, highly magnetized neutron stars formed in the supernova explosions at the end of the lifetime of massive stars. By converting their enormous rotational energy into powerful outflows of relativistic particles, pulsars inflate highly magnetized bubbles of high‑energy particles around themselves, known as pulsar wind nebulae (PWNe). Crucially, the total power available for particle acceleration can be directly inferred from precise pulsar timing measurements, making these systems, in theory, cleaner and more predictable than other candidate accelerators.

However, PWNe undergo a strong evolution during their lifetime, which complicates the picture. Very young systems are expected to be compact, with particles still efficiently confined close to the pulsar inside an outward‑expanding bubble of relativistic particles. Only thousands to tens of thousands of years later does a reverse shock, generated as the shock of the supernova explosion sweep up surrounding interstellar material, propagate back towards the center, crushing and distorting the nebula. At this point, instabilities can develop that allow particles to escape and diffuse over large distances. Extended gamma‑ray structures are therefore generally associated with evolved pulsars, not with the youngest members of the population [1].

HESS J1813–178 (SOM 2005/07) appeared, for a long time, to fit neatly into this established framework. The source is associated with one of the youngest and most energetic pulsars in our Galaxy, PSR J1813–1749, with an age inferred from its rotational energy loss of only about 5,000 years. Early very‑high‑energy gamma‑ray observations by H.E.S.S. revealed a compact nebula, fully consistent with expectations for such a young object [2]. At first glance, HESS J1813–178 seemed to be a textbook example of an early‑stage PWN.

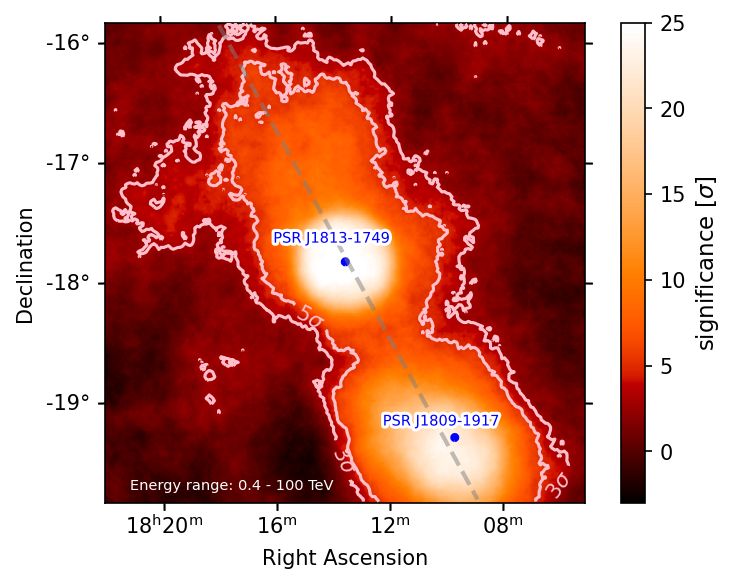

This tidy picture began to crumble with observations at other gamma‑ray energies [3,4] and with improvements in reconstruction and analysis techniques, which revealed additional emission, encompassing the previously detected compact nebula [5]. This extended emission, which can be seen in Figure 1, spans several tens of parsecs, far larger than expected for a nebula only a few thousand years old.

In our standard evolutionary models, the reverse shock reaches the PWN only after more than 10,000 years [1]. Explaining the observations would therefore require either an unusually early formation of the reverse shock, leading to a premature disruption of the magnetized bubble around the young pulsar, or a fundamental gap in our understanding of particle confinement and transport in very young PWNe. In both cases, specific environmental conditions in the region around PSR J1813–1749 may allow either highly relativistic particles to diffuse into the surrounding interstellar medium long before the expected timescales, or an early formation of the reverse shock.

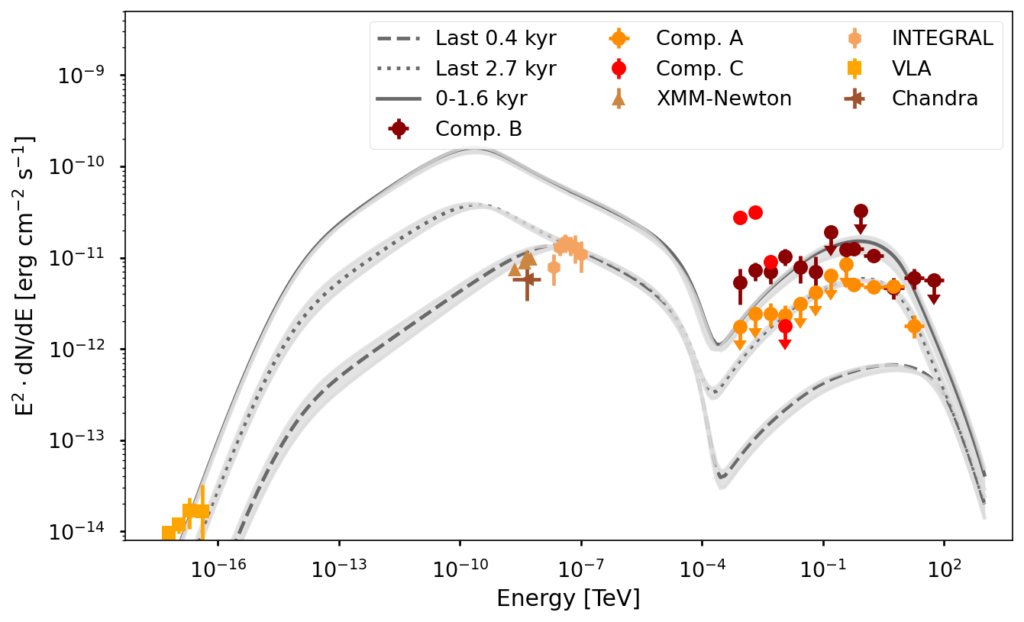

This scenario is supported by simulating the evolution of a population of relativistic particles originating from the pulsar, and comparing their expected emission to the observed emission from HESS J1813–178. Figure 2 shows that this simulated population can describe the emission well. However, the pulsar resides in a particularly complex environment and is not the only object capable of accelerating particles to extreme energies. The spatial extent of the emission encompasses not only PSR J1813–1749 and its surrounding nebula, but also the supernova remnant in which the pulsar was born (G012.7–00.0) as well as the nearby open stellar cluster Cl J1813–178. These spatial coincidences raise the question of whether the extended gamma-ray emission is indeed powered by the pulsar at all. An alternative interpretation is that the gamma rays originate from particles accelerated at the shock fronts of the supernova remnant or the stellar cluster and subsequently interacting with ambient gas. However, this scenario comes with its own challenges: reproducing the observed gamma-ray brightness would require either unrealistically high ambient gas densities or an unphysically efficient conversion of kinetic energy into relativistic particles.

Neither scenario is fully satisfactory, and it is precisely this tension that makes HESS J1813–178 so intriguing. Whether it represents an extreme outlier within the known PWN population or instead points to a very efficient particle acceleration in stellar clusters, the source forces us to question long‑held assumptions about how and when high‑energy particles escape their birth environments. HESS J1813–178 thus joins a growing list of gamma‑ray sources that appear deceptively ordinary at first glance, yet reveal unexpected behavior when observed with sufficient sensitivity and angular resolution. As new facilities come online and existing observatories continue to refine their analyses, sources like this remind us that even well‑studied classes of objects can still surprise us, and that the pathways by which cosmic rays are released into our Galaxy may be more diverse than we once thought.

References

[1] Giacinti, G., Mitchell, A. M. W., López-Coto, R., et al. 2020, A&A, 636, A113

[2] H.E.S.S. Collaboration, 2005, Science, 307, 1938

[3] Araya, M. 2018, ApJ, 859, 69

[4] HAWC Collaboration, 2020, ApJ, 905, 76

[5] H.E.S.S. Collaboration, 2024, A&A, 686, A149

[6] Helfand, D. J., Gotthelf, E. V., Halpern, J. P., et al. 2007, ApJ, 665, 1297

[7] Brogan, C. L., Gaensler, B. M., Gelfand, J. D., et al. 2005b, ApJ, 629, L105

[8] Ubertini, P., Bassani, L., Malizia, A., et al. 2005, ApJ, 629, L109

[9] Funk, S., Hinton, J. A., Moriguchi, Y., et al. 2007, A&A, 470, 249